Dark matter—one of the most widely accepted yet most contentious concepts in modern cosmology—remains the unseen scaffolding that binds the Universe together. Within our familiar Solar System, gravity behaves exactly as expected: the masses of the Sun, planets, and smaller bodies are sufficient to account for every observed gravitational effect. Apply general relativity, and the predicted orbits, velocities, and trajectories match observations with astonishing precision.

However, when we step beyond this local neighbourhood to the scale of the Milky Way, galaxy groups, clusters, and ultimately the vast cosmic web, the picture changes dramatically. The ordinary matter we know—everything composed of protons, neutrons, and electrons—falls far short of explaining the gravitational phenomena we observe. Something else must be present: an invisible, collisionless component with mass, capable of restoring concordance between theory and observation. This elusive ingredient is what we call dark matter.

On galactic and sub-galactic scales, alternative explanations do exist, including modified theories of gravity. MOND, the most prominent example, can reproduce many small-scale observations with surprising success. Fascinatingly, ongoing studies of “wide binaries” may soon offer a direct test distinguishing modified gravity from genuine dark matter. Yet, once we move to larger scales—especially the violent collisions of galaxy clusters—modified-gravity models rapidly fail, whereas dark matter continues to describe the data robustly.

But is this conclusion unassailable? Some proponents of modified gravity raise two principal objections, particularly concerning systems such as the Bullet Cluster, often heralded as definitive evidence for dark matter. Are these objections compelling, or do they fall apart under scrutiny? To answer this, we must examine the physics behind these controversial claims.

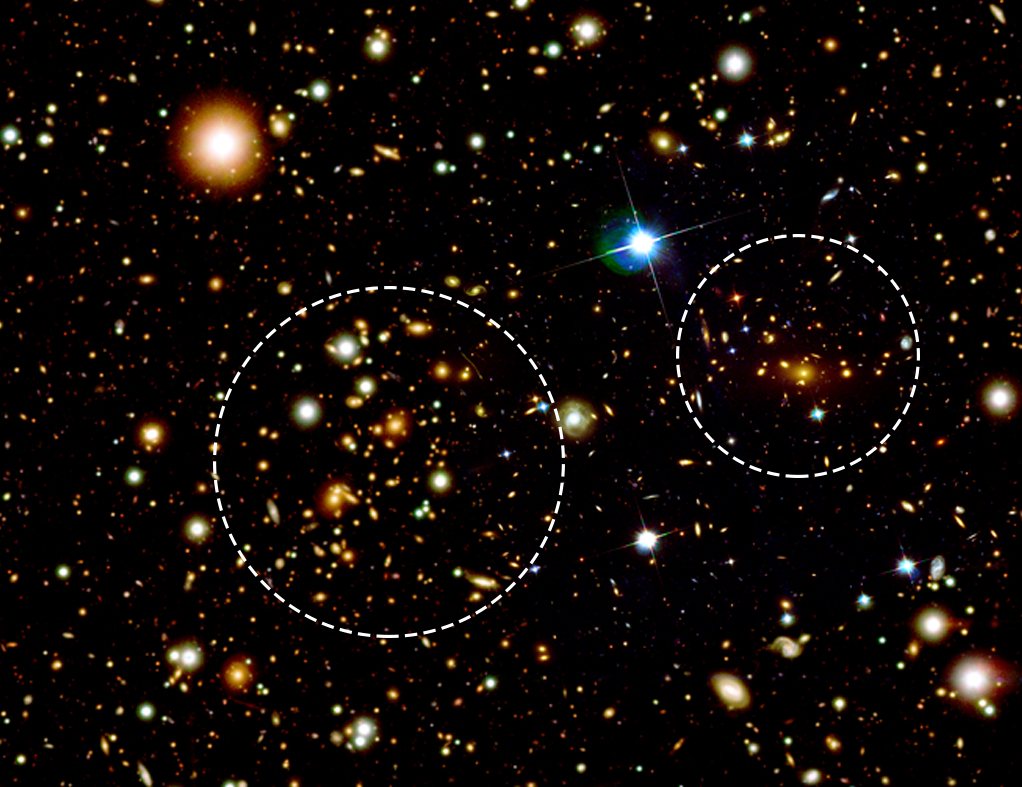

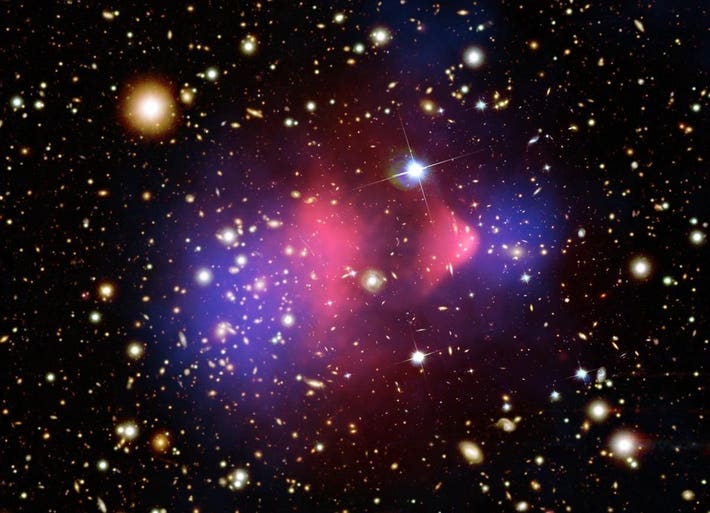

The Bullet Cluster, shown here, appears in optical wavelengths as two neighbouring concentrations of galaxies—two massive clusters that are not merely projected together on the sky but physically interacting in three-dimensional space. We infer the nature of this interaction from two independent observational signals.

The first arises from X-ray observations. Whereas optical light reveals luminous stars, X-rays trace gas heated to extreme temperatures. Such gas permeates galaxies and, crucially, the intracluster medium between galaxies in bound structures like clusters. X-ray imaging of the Bullet Cluster shows a vast reservoir of superheated gas and plasma between the two clusters, unmistakably indicating a recent high-velocity collision—about 5,000 km/s—and revealing a prominent shock front.

The second signal comes from gravitational lensing, which depends solely on mass, irrespective of its temperature or luminosity. Mass along the line of sight bends and distorts the shapes of background galaxies. Strong lensing produces arcs, rings, and multiple images—like reflections in a funhouse mirror—while weak lensing subtly shears background galaxies into aligned ellipses. It is this weak lensing that allows us to reconstruct the large-scale mass distribution of a cluster.

In the Bullet Cluster, weak-lensing maps reveal that the bulk of the mass is not associated with the X-ray-bright gas—which has been slowed and displaced during the collision—but rather with the galaxies themselves, which passed through largely unimpeded. The discrepancy between the location of the visible matter and the location of most of the mass exceeds 5σ, the gold standard for discovery in astrophysics and particle physics. On cluster scales and in colliding-cluster systems, the evidence for dark matter vastly outweighs anything offered by modified gravity alone.

Yet critics argue that lensing traces mass concentration, not total mass, and that the Bullet Cluster’s collision velocity is improbably high within the ΛCDM framework. These claims appear frequently in the MOND literature—but do they withstand detailed examination?

Physically, gravitational lensing responds both to local density peaks and to extended mass distributions. Strong lensing demands high concentrations, capable of magnifying background galaxies by factors of tens to thousands. Weak lensing, however, is sensitive even to diffuse mass, making it the most informative tool for reconstructing the full mass distribution of galaxy clusters.

This was firmly established over two decades ago. A seminal Nature paper by Gus Evrard (1998) reconstructed a cluster’s mass distribution from lensing data. The resulting map displayed prominent peaks associated with individual galaxies but, more importantly, revealed a broad, diffuse component at the cluster’s centre. More than 80% of the cluster’s total mass resided not in galaxies but in the intracluster medium—precisely what the dark-matter paradigm predicts. Ordinary matter collapses into dense structures such as stars and galaxies, but dark matter remains diffuse because its collisionless nature prevents it from forming compact clumps.

Even so, dark matter is not perfectly smooth. Simulations predict that each massive halo should be populated by numerous dark-matter subhaloes—small, self-bound structures embedded within larger systems. Lens reconstruction combining strong and weak lensing, along with intracluster light, confirms the presence of these substructures. They manifest as additional mass concentrations beyond anything associated with luminous galaxies.

Strong-lensing systems in galaxies—especially quadruple-image configurations—further constrain dark-matter structure on small scales. Minute differences in the brightness, magnification, and position of each image indicate whether dark matter is smooth or clumpy. A landmark 2020 study detected discrepancies at the 0.1% level, implying the presence of subhaloes and ruling out warm, hot, or otherwise fast-moving dark matter, which would erase such small-scale structure. The data require cold dark matter, with abundantly clumpy substructure.

Is the Bullet Cluster a rare cosmic anomaly? Consider the “Coathanger” asterism: ten bright, apparently clustered stars within a single square degree of sky. Statistically, such an alignment should be extraordinarily rare—yet the stars are unrelated. It is a chance superposition. Similarly, the Bullet Cluster’s collision speed may appear extreme, but statistical studies and cosmological simulations disagree on its rarity. Some estimate a probability below 5σ; others find it unusual but not inconsistent with ΛCDM; still others deem it entirely ordinary.

More importantly, we now have dozens of colliding-cluster systems with both X-ray and lensing measurements. In every case, heated gas betrays the collision, and in every case, the total mass distribution is offset from the baryonic matter. Some collisions are as fast as the Bullet Cluster; many are slower and firmly within ΛCDM expectations. The pattern is universal: galaxies and dark matter pass through, while gas lags behind.

Modified-gravity models simply cannot reproduce this behaviour without introducing an additional invisible mass component—effectively reinventing dark matter under a different name. On the largest scales, their predictive power collapses.

The visible Universe—stars, gas, and dust—constitutes barely 10% of all matter. The remaining 90% is dark matter, first inferred by Fritz Zwicky in 1933 from the high velocities within the Coma Cluster. Later, in the 1970s, flat galactic rotation curves provided further compelling evidence: stars at large radii orbit so quickly that, without additional unseen mass, they would escape their galaxies entirely.

Galaxy clusters act as gravitational lenses, producing stretched arcs of background galaxies. By analysing these distortions, astronomers determine cluster masses and find that luminous galaxies account for only a small fraction of the total. Collisions such as the Bullet Cluster reveal even more strikingly that dark matter behaves as a collisionless component, passing through itself and ordinary matter with minimal interaction.

But detecting dark matter is only the beginning. Understanding what it is remains an unsolved problem.

For decades, astronomers considered massive compact objects—dead stars, black holes, and faint astrophysical bodies—as potential dark-matter candidates. Microlensing experiments did detect some such objects, but far too few to account for the Universe’s missing mass.

This led researchers to consider non-baryonic particles. Cold dark matter, comprising slow-moving particles in the early Universe, naturally produces the hierarchical structure we observe today—from small haloes merging into massive clusters. Yet none of the hypothetical particles proposed so far has been confirmed.

Supersymmetry posits that every Standard-Model particle has a massive partner. These weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs), particularly the lightest neutralino, became leading dark-matter candidates. Another contender is the axion, a remarkably light particle originally proposed to solve the strong-CP problem. Unlike WIMPs, axions act more like force carriers, akin to photons but vastly lighter, requiring enormous numbers to make up the cosmic dark-matter density.

Despite decades of effort, neither WIMPs nor axions have yet been detected. Their elusiveness stems from their extraordinarily weak interactions: they do not emit, absorb, or reflect light, and they collide only rarely with ordinary particles.

Direct-detection experiments aim to capture the tiny recoil of an atomic nucleus struck by a WIMP. Indirect searches look for annihilation products such as γ-rays, positrons, or neutrinos. Axion experiments rely on the particle converting into photons in strong magnetic fields. Meanwhile, particle accelerators attempt to create dark-matter candidates directly.

The Sun’s orbit around the Milky Way carries the Solar System through a halo of dark matter. Although hundreds of millions of WIMPs may pass through a square metre each second, their interactions are so feeble that only detectors placed deep underground—shielded from cosmic rays and background radiation—have any hope of observing them.

Yet despite formidable challenges, the search continues. Every improved limit, every new experiment, and every astrophysical observation narrows the possibilities, bringing us closer to identifying the particles that make up the vast, invisible framework of the cosmos.